E. L. Godkin and the Literific’s Origins (1850-60)

After Queen’s College Belfast opened its doors to students in 1849, there was very little by way of social life for the students. The College was entirely focused upon academia and had little interest beyond that, leaving it to the students to create a social life for themselves by organising various clubs and societies.

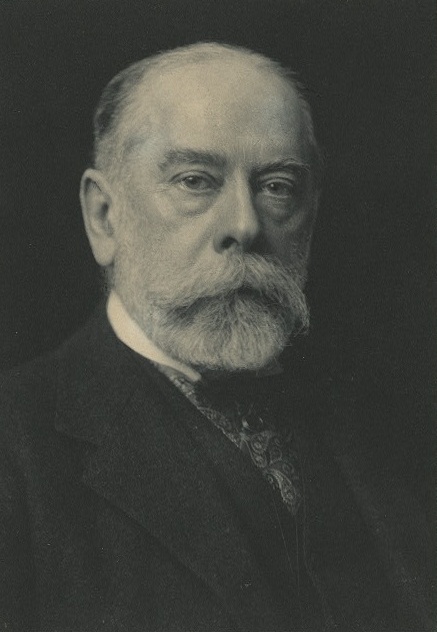

The first society to be established was the Literary and Scientific Society, referred to as the “Literific” by its members. Their first President was Edwin Lawrence Godkin, who would go on to act as editor on The Nation and Evening Standard.

Originally, the society took quite a different form than it currently possesses. For one matter, it was a more exclusive society, with new members having to be “elected” by others. More importantly, the Literific was a paper-reading society, wherein speakers would essentially read out their essays and present lectures. In the public meetings these were often professors, functioning as guest speakers. At private meetings, the Literific seems to have taken on a character closer to its modern one, with members reading papers and being given criticism on them by their peers.

An interesting aspect to note is that in this early era, instead of being banned from “party polemic” as they are today, members were banned from presenting any papers that referred to “politics or religious polemics”, in line with the traditional censorship of dissent in the 19th Century. The Literific, however, from the very start, found ways of evading this restriction and championing free thought.

One common loophole was the use of “historical” papers to indirectly critique modern politics. Godkin himself once read a “historical” paper on Lord Eldon – an infamously traditionalist member of the old Tory Party. Bearing in mind that Godkin was what historians Moody and Beckett call a “militant liberal”, it is hard not to read this as intended as a critique of the Conservative Party, which replaced the Tories in 1834.

Despite its leniency with such rules, the Literific quickly grew to great prominence among the student body and enjoyed the patronage of the president of Queen’s College himself.

Difficulties Arise (1860-86)

Despite this early success, difficulties emerged during the 1860s. While the Literific remained prominent and well-attended in the late 60s, tensions arose. This is likely due to a heated political climate in the aftermath of the 1867 Fenian Rising and the subsequent resurgence of nationalist politics in Ireland. Moody and Beckett claim tensions escalated to the point where there was “two parties” within the Literific. Council elections became hotly contested and eventually a splinter faction emerged in 1868, known as the “History and Critical Society”, likely comprised of the society’s more conservative and unionist members.

On top of this, the Literific’s own prominence began to cause problems. In 1869, a paper on “The spirit of Irish history” drew enough controversy that Conservative MP Robert Peel Dawson brought it up in parliament, describing it as containing some “very questionable expressions”. This led to an investigation by the Chief Secretary for Ireland into whether the paper was seditious and indeed whether the Literific was therefore seditious. Thankfully, these difficulties would prove short-lived. The Literific was found innocent in the inquiry and in 1872 the History and Critical Society agreed to rejoin the Literific.

There was another dip in popularity in the early 1880s. Attendance to private meetings is noted as being “low” several times in the minutes between 1880 and 1885. A contributing factor was a second split in 1883, resulting in the formation of the Junior Debating Society. However, this proved a significant, even positive development.

The Literific Renaissance (1886-1960)

On 24 November 1885 it was revealed by Vice-President McLaren that negotiations had been ongoing between the Literific and the Debating Society to organise an amalgamation. Aside from creating an unreasonably large council for the 1885-86 session, this saved and rejuvenated the society. Aside from the resignation of the Literific’s President, the merger was passed “unanimously”. Two weeks later, on 8 December, the society held its first ever debate on “the comparative merits of Republican and Monarchical Government”. Such debates would grow in importance until eventually they would supplant the Literific’s traditional paper-readings completely. Therefore, the merger of 24 November could be described as the start of a Renaissance of sorts for the society. For the next 75 years the society seems to have only experienced growth in membership and prominence, and saw several important reforms.

The 1880s also saw the admission of women to the society for the first time ever, though it is unclear when exactly and when they were allowed to become members. Moody and Beckett suggest they were admitted on 16 March 1886. Later on, during the First World War, the society would have a female president, several years before women were granted universal suffrage.

The society also became quite politically significant, drawing important guests and being viewed as an important bastion of public opinion on some issues. In 1907 the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Augustine Birrell, consulted members of the Literific for their opinions on the conversion of Queen’s College into a University. In February 1957, Eamon de Valera addressed a huge audience at the Literific. Several members from the 1950s testify that meetings regularly saw hundreds of attendees.

Decline and Collapse (1960-67)

However, this fortune eventually ran out in the 1960s and the Literific rapidly declined following several major setbacks to its reputation and prominence. Firstly, in 1962, the Student Representative Council (now the SU) banned the press and public from attending meetings of all clubs and societies. The SRC’s then-President Andy Duffin explained himself in an interview with the Gown in that year. He felt, in the face of rising sectarian tensions, that the SRC should be combatting the “slant towards easily sensationalised topics”, and that it was outside the “proper sphere of activity” for some societies to centre themselves as the “hub of political opinion”. If I might guess at what he actually means by this, he thought the Literific (among others) were rabble-rousers who were embarrassing the university and drawing too much controversy. You didn’t have to be so oblique about it, Andy.

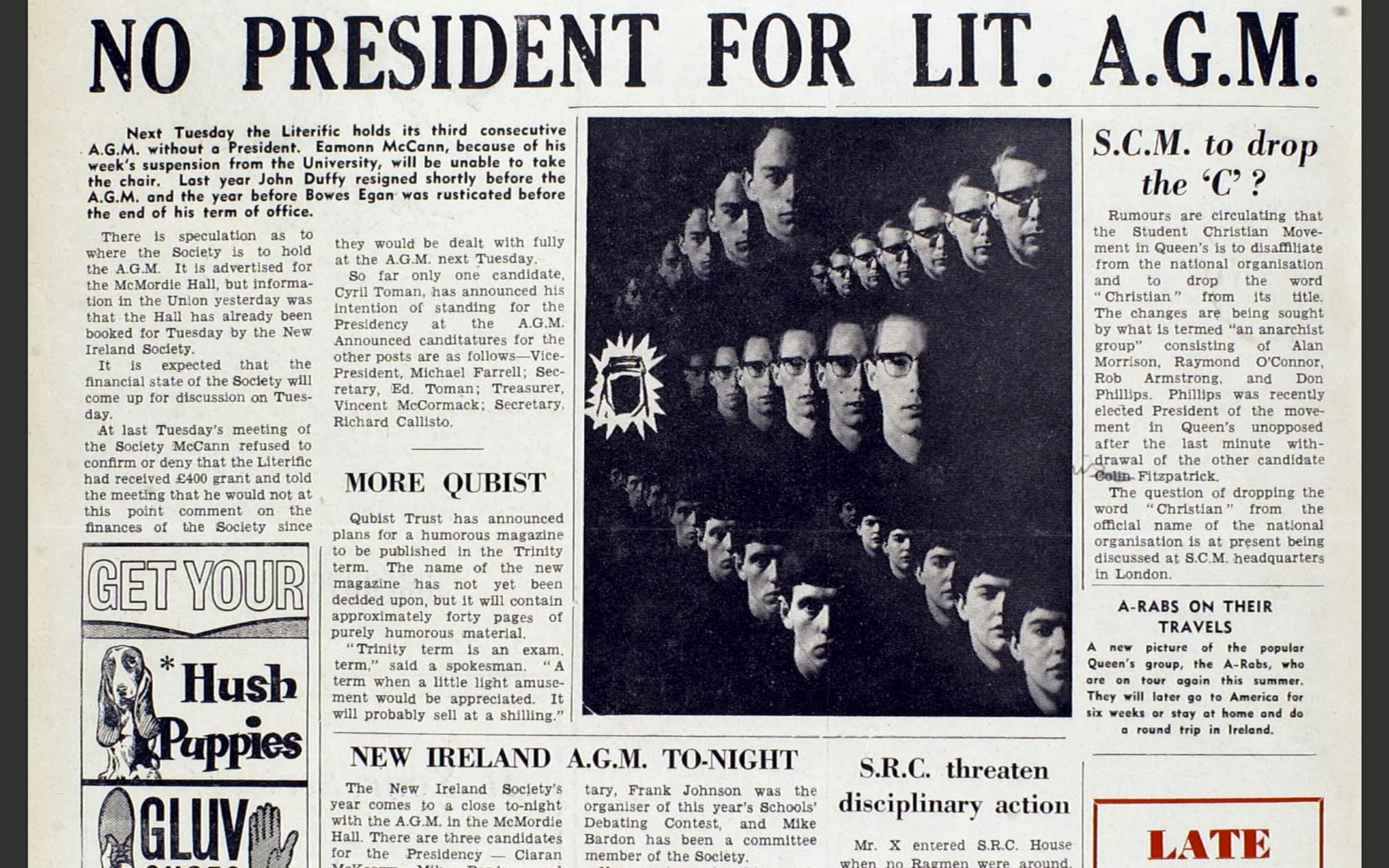

The second major blow is arguably the most damaging and is less one injury than a continuously damaging tendency. Between 1962 and 1965, the society seems to have fallen into nothing short of total disorder and unruliness. Particularly disorderly was the 1964-5 session led by future MLA Eamon McCann. In this session, a guest speaker identified as

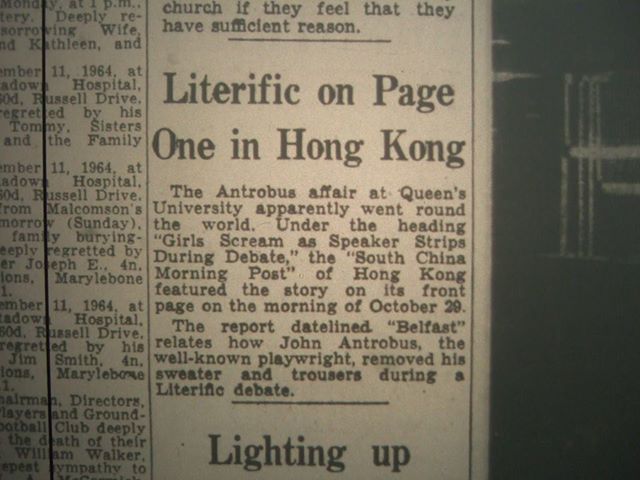

John Antrobus, the famous playwright and Carry On writer, stripped off in front of the Literific, leading to the society being disbanded by the SRC for several weeks. Word of this incident spread as far as Hong Kong. An account of the incident appeared on page 1 of the South China Morning Post. In a less spectacular episode several months later, McCann himself stole bottles of wine from the Botanic Inn and was suspended for a week from the university, leaving the Literific without a President at the AGM for the third year in a row.

A third major blow was the decision to amend the constitution to allow the society to abandon its impartiality in favour of an overtly Irish nationalist stance. In October 1964, a motion was proposed by a “Mr Puthucheary”, which moved that the Literific establish a “sub-committee to get in touch with interested bodies with a view to protesting against colonialism”. Understandably, this caused some controversy, with the Gown writing this move was seen “in responsible circles as a distortion of all the Literific has ever represented, and as minimising the possibility of free debate”. This may have quite understandably alienated a large number of students, particularly those of a unionist background and those who were interested in the principal and “sport” of debate.

But hey, at least Eamon won best speaker at the Irish Times Debating Competition! That’s something, right? Right?

This burst of infamy and disregard for impartiality coincided with a steep decline in membership. By December 1965, the Literific wasn’t able to muster the 20 members necessary to hold a debate, forcing them to disband that meeting. A brief attempt was made at resurrection in 1966 via the use of guest speakers instead of students, but the cause was quickly viewed as hopeless.

And so, on Tuesday 7 March 1967, the Literific agreed to dissolve itself into the new Union Debating Society. Rory McShane, who proposed the dissolution, said this: “The Literific at present is not the best platform for debating at Queen’s. There is obviously a need for a Society where all members of the University can feel they can come and air their views”. And so it was dead. We lost our way and paid the price.

Life After Collapse (1967-2011)

Debating at Queen’s wasn’t dead, though. The Union Debating Society carried on and was quite successful for a time. Initially, all students were registered as members of the Union Debating Society when they joined the Student Union, a privilege the Literific had once held. However, its star eventually faded. It evolved into the Debating and Mooting Society, and nowadays operates under the wing of the Law Society.

Resurrection (2011-Present)

However, as you might have guess from the existence of this website, we have returned. How on earth did we manage to come back from a famous comedian stripping off before our members? Well, over the years, the Debating and Mooting Society grew more and more interested in mooting instead of traditional debating and a gap in the market emerged. A gap that would be filled by one Paul Francis Shannon, President of the 163rd Session, affectionately dubbed the “eternal leader” by modern members. Under his guidance the Literific reemerged from Debating and Mooting in 2011 and has since prospered once more, steadily growing over the years.

Now, as we go into our 174th Session, we may not get hundreds of members per meeting but we can always aim high. We have launched the LitTalks and Great Debates series to give students the ability to engage with prominent speakers. We are contenders in the Irish Times Competition once again. We have meetings once a week on Thursdays and, above all, we have learned from the past – learned something even Godkin seems to have failed to value. We know that for a society to function it must cater to all members, regardless of their community or political affiliation. Must make them feel welcome and respected. Must make them feel as though they are not entering into one party meeting or another, but entering into a forum where they can talk with their fellow men and understand them better, in the hope that we all may become better. And by understanding this failure of our past, we will be ready for our future.